Vulnerable Populations in Oncology Research:

Challenges and Opportunities for Participation of Persons with HIV/AIDS in Cancer Therapy Clinical Trials

April 2019

Although progress has been made in the global fight against HIV/AIDS, the epidemic continues in the United States (U.S.) and international community1. Nearly 37 million people worldwide are living with HIV, and 9.4 million of those infected are not aware of their HIV status. Globally, AIDS-related deaths dropped by 45 percent since their peak in 2004. Yet the rate of HIV transmission remains unacceptably high, with 1.8 million new infections occurring worldwide in 2017 alone equating to about 5,000 new infections per day2.

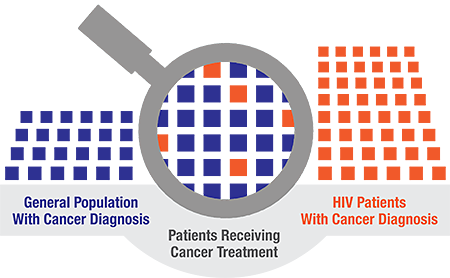

In the U.S., there are 1.2 million people living with HIV (PLWH), and in 2017, approximately 7,760 of these individuals were diagnosed with cancer. This indicates PLWH are 50% more likely to be diagnosed with cancer than the general population3. In fact, cancer is now reported as the leading cause of death among people with HIV4. Despite the higher cancer incidence rate in the HIV-positive population, research has shown that PLWH who have cancer are significantly less likely to be treated for cancer5.

It is important to mention that there are no specific exclusions provided in the FDA label expansion for HIV-positive patients. Physicians can prescribe off label at their discretion. However, PLWH have been historically excluded from participating in clinical trials of new cancer treatments because of safety concerns regarding drug interactions. This may significantly delay PLWH from accessing potentially life-saving cancer therapies. This issue is especially relevant in the case of immunotherapy, a new and promising type of cancer therapy. For instance, clinical trials of a new category of immunotherapies called immune checkpoint inhibitor (ICI) therapy have historically excluded patients with HIV infection and therefore, the safety and efficacy profile of ICIs is unknown in this underrepresented population6.

Certain immunotherapies are approved to treat cancers that HIV-positive individuals are at increased risk of developing such as non-small cell lung cancer, but studies to determine whether these treatments are safe or effective for PLWH have not yet provided definitive results. Notably, a recent study published in JAMA Oncology in 2019 showed that ICI therapy appears to be safe and efficacious in HIV-infected individuals with advanced-stage cancer6.

The types of cancers have increased in the HIV-infected population. With the availability of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART), PLWH can now expect to live as long as those who are not HIV-infected, and the HIV population is also developing cancers that are common in older age groups. Longer life expectancy is already evident: by 2016, 5.8 million PLWH worldwide were over the age of 507,and in the U.S., nearly half of people with diagnosed HIV were also age 50 or older8. This is a welcome development, but aging with HIV also brings another set of issues to the table. Some are common to those faced with managing any chronic condition or late-in-life illness such as cardiovascular disease, lung disease, HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders, and liver disease (including hepatitis B and hepatitis C), which present a growing challenge to the health and human services system across all sectors, and at all levels9.

HIV positive patients face many challenges for participation in cancer therapy clinical trials. For instance, the CD4 count has been an important parameter used by physicians to decide whether to start their patients on HAART. This is also a critical factor in HIV management and in guiding clinical treatment. Nevertheless, there is significant intraindividual variability in CD4 count measurement in even healthy adult subjects. Several factors contribute to this variability such as infection, medications, or other chronic conditions. In the same vein, immunotherapies may be less safe or efficacious in the HIV-infected population which is immunocompromised and especially an issue for people whose HIV infection is poorly controlled. In addition, medicines used to treat HIV infection (HAART) may interact with certain cancer drugs. This could lead to more side effects or less efficacy of cancer therapies in HIV-positive individuals than in HIV-negative individuals. These complications can also make it difficult to interpret and apply the results of cancer clinical trials to the HIV infected population 10. A national survey of medical and radiation oncologists showed cancer care providers were less likely to offer cancer treatment to HIV-infected patients if they have concerns about toxicity and efficacy of cancer therapy and are more likely to offer treatment if they are comfortable discussing adverse effects and prognosis. Most respondents felt currently existing cancer management guidelines were insufficient for management of HIV-infected patients 11.

Despite these challenges, people with HIV should not be excluded from receiving cancer therapies. For many years, the National Cancer Institute (NCI) has recommended people with HIV not be arbitrarily excluded from cancer clinical trials, and NCI has enrolled PLWH in immunotherapy trials. One NCI-sponsored trial conducted by its HIV and AIDS Malignancy Branch and the Cancer Immunotherapy Trials Network (CITN), is testing the immunotherapy drug pembrolizumab specifically in people with advanced cancer who are HIV- positive. Interim results showed pembrolizumab had an acceptable safety profile for HIV-positive patients, and there were no negative interactions between pembrolizumab and HAART12. These results appear to support inclusion of HIV-positive people in immunotherapy clinical trials.

The NCI has specific guidelines regarding inclusion of HIV positive individuals on clinical trials. The guidelines clearly state that exclusion of HIV-positive individuals from a trial must be based on compelling scientific grounds that show that exclusion is necessary for the conduct of the research, or that the individual does not meet essential eligibility requirements of the trial. Such grounds for exclusion must be reflected in the clinical trials eligibility criteria which may include laboratory, animal, or clinical evidence suggesting that a treatment may be associated with increased adverse effects for individuals with immune deficiencies, or if HIV-associated symptoms may preclude accurate assessment of toxicity or response to the treatment13. In February 2018, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) released new clinical practice guidelines on cancer care for PLWH. The guidelines emphasize that most PLWH who develop cancer should be offered the same cancer therapies as HIV-negative individuals, and modifications to cancer treatment should not be made solely on the basis of HIV status 14.

The changing epidemiology of cancer in HIV poses challenges as well as opportunities for participation of persons with HIV in oncology research. Interpretation of clinical trials to guide therapy for those with HIV infection and cancer largely depends on data that does not include HIV -infected patients. The ability to extend clinical trial findings to populations not included in clinical trials remains problematic for a variety of populations, including those with HIV or AIDS. Careful prioritization of studies designed to bridge this gap is needed.

HIV disease can be viewed as a comorbid condition and assessed for its potential to impact cancer therapy. Patients with more advanced HIV disease and related complications may be more delicate and therefore the selected approach to cancer therapy must consider these factors. Similarly, the decision to enroll patients in clinical trials, and associated entry criteria for trial participation must take HIV status into account.

As cancer becomes an increasingly important cause of mortality in the HIV-infected population, improving cancer outcomes in the HIV-infected population is of paramount importance. Broader clinical trial access will be a major advance for people with HIV and cancer. Including people with HIV on more clinical trials can lead to tremendous changes in how cancer is treated in these patients, with the potential to save many lives. Inclusion of HIV-seropositive individuals with cancer in clinical trials enables access to novel treatments that may be clinically efficacious and assures that research findings from cancer research are generalizable to representative populations. Also, addressing the underrepresentation of HIV infected patients in cancer clinical trials enhances care coordination between oncologists and HIV specialists and may reduce cancer treatment disparities for HIV-infected patients with cancer11. Finally, pharmaceutical companies will have evidence to expand subscribing labels to include/exclude the HIV population.

TRI has always recognized the importance of enhancing minority representation in oncology research, with particular attention paid to those identified as underrepresented and underserved. With this awareness, we provide a wide spectrum of services to the life sciences industry, such as the development and implementation of participant recruitment, and retention campaigns. TRI also has vast experience in conducting clinical trials that affect HIV-seropositive individuals. Our long-standing clinical trial expertise allows us to satisfy clinical trial regulations, protocol development, and operations. Finally, TRI acknowledges the importance of advocacy for inclusiveness in oncology clinical trials, because translation of research evidence into clinical practice is effective only in populations that are adequately represented.

Footnotes

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 2018. HIV/AIDS. Basic Statistics. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/basics/statistics.html

- Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS). (2018). Global HIV & AIDS statistics 2018 fact sheet. Available at: http://www.unaids.org/en/resources/fact-sheet

- Lee, L. (2018). NCCN: New Guidelines on Care of HIV Concurrent With Cancer. Oncology journal. Cancer Network. Available at: http://www.cancernetwork.com/treatment-guidelines/nccn-new-guidelines-care-hiv-concurrent-cancer

- The National Comprehensive Cancer Network. (2018). New NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology for Cancer in People Living With HIV seek to reduce unnecessary, deadly cancer care gaps. Available at: https://www.nccn.org/about/news/newsinfo.aspx?NewsID=1010

- Suneja G, Lin CC, Simard EP, et al. Disparities in cancer treatment among patients infected with the human immunodeficiency virus. Cancer 2016;122:2399-2407. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27187086. And Suneja G, Shiels MS, Angulo R, et al. Cancer treatment disparities in HIV-infected individuals in the United States. J Clin Oncol 2014;32:2344-2350. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24982448.

- Cook MR, Kim C. Safety and Efficacy of Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor Therapy in Patients With HIV Infection and Advanced-Stage Cancer: A Systematic Review. JAMA Oncol. Published online February 07, 2019. doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.6737

- UNAIDS. (2016). UNAIDS PCB session on ageing and HIV reaffirms that an ageing population of people living with HIV is a measure of success. 39TH meeting of the PBC. Available at: http://www.unaids.org/en/resources/presscentre/featurestories/2016/december/20161208_HIV-and-ageing

- Centers for Disease Control and Provention (CDC). (2018). HIV Among People Aged 50 and Older. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/group/age/olderamericans/index.html

- Sean Cahill, PhD; Blair Darnell, et. al., (2010). Growing Older with the Epidemic: HIV and Aging. Available at: http://www.gmhc.org/files/editor/file/a_pa_aging10_emb2.pdf

- Little RF. Cancer clinical trials in persons with HIV infection. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2017 Jan;12(1):84-88. Review. PubMed PMID: 27559711; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC5257291

- Suneja, G., Boyer, M., Yehia, B. R., Shiels, M. S., Engels, E. A., Bekelman, J. E., & Long, J. A. (2015). Cancer Treatment in Patients With HIV Infection and Non-AIDS-Defining Cancers: A Survey of US Oncologists. Journal of oncology practice, 11(3), e380-7

- Sharon E, Uldrick T. (2017). Expanding Cancer Clinical Trial Access for Patients with HIV. National Cancer Institute. Available at: https://www.cancer.gov/news-events/cancer-currents-blog/2017/immunotherapy-cancer-HIV

- National Cancer Institute. (2008). Guidelines Regarding the Inclusion of Cancer Survivors and HIV-Positive Individuals on Clinical Trials. Available at: https://ctep.cancer.gov/protocolDevelopment/policies_hiv.htm

- The National Comprehensive Cancer Network. (2018). New NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology for Cancer in People Living With HIV seek to reduce unnecessary, deadly cancer care gaps. Available at: https://www.nccn.org/about/news/newsinfo.aspx?NewsID=1010

About the Author

Dr. Carlos M. Naranjo is a bilingual, International Medical Doctor (MD) from Los Andes University in Venezuela. Currently, he is pursuing a Master in Public Health at George Washington University. At TRI, he provides Safety and Pharmacovigilance for clinical trials. A member of the National Hispanic Medical Association, his most recent article "Special Populations Underrepresented in Oncology Research: Challenges and Solutions to Engage the Hispanic Population" was published in the TRIbune and Applied Clinical Trials.